Courtesy photo Denese Sebek Kimpston

Courtesy photo Denese Sebek Kimpston

Gary Eugene Sebek

Gary Eugene Sebek

Homicide

Gary Eugene Sebek

20 YOA

DOB: Dec. 29, 1947

Dave Ware Apartments

1609 Main Street

Hamburg, Iowa

Fremont County

BCI/DCI Case File No.: 68424

FBI File No.: 95-144254

Est. Date of Death: March 4, 1968

Gary Eugene Sebek, 20, spent the last day of his life going to work in the morning, being called away to witness the birth of his second child – a son – and leaving the hospital late that evening to return to his Hamburg, Iowa home, where he’d be slain that same night and his body removed from the premises.

His disappearance on Monday night, March 4, 1968, began as a missing persons case, and then was investigated as a suspected homicide after investigators seized a bloody sofa from the 1609 Main Street apartment Sebek shared with his wife and young daughter. The FBI got involved, and questions even surfaced as to whether Sebek simply disappeared in efforts to avoid the draft.

He had not.

Sebek’s whereabouts on his last day alive are clearly documented by numerous eyewitness accounts. But someone had, however, wanted him gone.

The Last Day

Fremont County in Iowa

Fremont County in Iowa

Hamburg in Fremont County

Hamburg in Fremont County

At 5:30 a.m. Monday, March 4, 1968, co-worker Paul Bashaw picked up Sebek and drove to Crown Line Plastic Company in Nebraska City, Nebraska, where both Sebek and Bashaw worked. Later that morning, Sebek’s wife, Shirley (Moyer) Sebek, and Shirley’s sister, Janice Holland, arrived at the plastics plant to let Sebek know his wife was in labor. The three adults, along with the Sebek’s 2-year-old daughter, Lisa, travelled together to St. Mary’s Hospital in Nebraska City.

Sebek stayed at the hospital through his wife’s childbirth, and got to meet his newborn son, Patrick.

Around 10:30 p.m., Bill and Dena Siddens, friends of the Sebeks, gave Gary a ride back to Hamburg, and at approximately 11 p.m. dropped him off at the Main Street duplex.

Sebek neither reported to work nor came to the hospital to visit Shirley on Tuesday, and by day’s end, Shirley’s sister Janice and friend Dena would visit the Sebek apartment and discover a number of oddities that marked the beginning of nearly 50 years of unanswered questions.

Many things, however, were already well known and documented in statements provided to detectives both before and after Sebek’s disappearance:

- Sebek’s father-in-law, Victor Kenneth “Buck” Moyer, had taken in and raised Shirley and her brother, John, as young children, and Moyer’s obsession with Shirley went beyond a father’s concern for a daughter.

- Victor Moyer hated his son-in-law with such unabashed passion he’d told a number of individuals he could kill him (Page 2 of Supplementary Report from BCI Director R. D. Blair, dated May 15, 1968).

- Moyer told local businessmen that one day Gary would just disappear and that Shirley would then be coming back to him (Moyer).

- Gary Sebek so feared his father-in-law, that during periods when Moyer had forced the couple apart and Sebek stayed with his own father, he slept with the lights on at night and a gun under his bed.

- At the hospital on the same day Shirley gave birth, Victor Moyer confronted Gary Sebek and unashamedly argued that the new baby wasn’t even Sebek’s because he himself had fathered his (adoptive) daughter’s new son.

- Moyer dominated every aspect of the young couple’s life (in official Bureau of Criminal Investigation reports), eventually persuading Shirley to divorce Sebek. The couple, however, were still in love, and planned to remarry and move far away from Victor Moyers’ control — they’d talked about relocating to Florida — as soon as their second child was born.

The couple never got the chance.

Shirley Sebek “fears for own life”

Based on evidence the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office found in the Sebeks’ home, they felt confident they had a homicide on their hands, but knew that without a body or an eyewitness, they’d face many challenges proving murder in a court of law.

Courtesy photo Sue P., findagrave.com

Courtesy photo Sue P., findagrave.comShirley Ann Moyer Sebek

Two months after her husband’s disappearance, Shirley voluntarily submitted to two polygraph tests for the Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation — both of which she passed — and told authorities she believed Gary was dead, that her (adoptive) father had killed him, and that she also feared for her own life.

Thirteen months after Gary Sebek went missing — and by the time 40 law enforcement officials searched 240 acres of Moyer’s farm ground seeking clues to Sebek’s disappearance — Shirley Sebek made good on her promise to Gary to get out from under Moyer’s control; she relocated to Arkansas and eventually remarried.

She’d managed to get away, alive.

What really happened to Gary Sebek?

Sebek’s gravestone indicates his death occurred the same month he went missing, but his gravesite remains empty.

Allegations persist that Moyer had two accomplices who helped with removing Gary Sebek’s body from the Main Street apartment — one directly related to Moyer and the other the accomplice’s best friend — and though the allegedly primary accomplice remains alive today, the best friend, Gordon Gill Jr., supposedly consumed by guilt, later reached out to Sebek’s cousin, Kenneth Sebek, at the popcorn plant where Kenneth worked. Kenneth, who wasn’t yet free to take a break, asked Gill to wait and he’d speak with him then.

Instead, Gill allegedly went home, wrote a suicide note referencing details about the night of Sebek’s murder, and then took his own life.

Victor Moyer, who held a pilot’s license, purportedly flew a considerable distance down the Missouri River with his own best friend, also a pilot, where the two allegedly then dumped Sebek’s body.

Courtesy photo Sandy Thompson, findagrave.com

Courtesy photo Sandy Thompson, findagrave.comGary Sebek’s gravestone lists no specific day of death but reflects the month he went missing. His grave remains empty.

Based on Fremont County Sheriff’s Office reports, FBI files and letters, Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation court files and reports, statements provided to Iowa Cold Cases and numerous follow-up interviews conducted by Jody Ewing, Iowa Cold Cases takes a closer look at a case nearly a half-century cold.

Monday, March 4, 1968

Paul Bashaw and Gary Sebek arrive at the Crown Line Plastic Company in Nebraska City around 6 a.m.

Just before 7:30 a.m., Shirley Sebek goes to the Hamburg, Iowa, laundromat and phones her sister, Janice Holland, to say she’s in labor and needs a ride to the Nebraska City hospital. (The Sebeks had no home phone.) Janice Holland picks up Shirley and Lisa at the laundromat, and they stop at the plastics company to notify and pick up Gary Sebek before proceeding to St. Mary’s Hospital in Nebraska City.

Shortly after dropping off the Sebeks at the hospital, Janice heads back to Hamburg to the Sebek residence to get some clothing for Gary and Lisa. She finds the kitchen floor quite dirty, and, in the bathroom, a dry mop and a pail containing stale water. She gathers some of Gary’s and Lisa’s dirty clothes and takes them with her to wash at home.

At the hospital, Shirley gives birth to a baby boy.

Around 10:30 p.m., Bill and Dena Siddens leave the hospital with Gary Sebek and give him a ride back to Hamburg. They drop him off at the Sebek residence at approximately 11 p.m.

Tuesday, March 5, 1968

Around 5:30 a.m., Paul Bashaw stops by the Sebek home as usual to pick up Gary for work. Bashaw sees lights on in the house and can hear the home’s radio playing loudly. When Sebek doesn’t come out to the car, Bashaw exits the vehicle and approaches the duplex’s kitchen door. He finds the door open, and after entering the home finds Gary’s cigarettes on the kitchen table. He calls out for Sebek, glances briefly into each room, and, finding no one at the residence, gets back into his car and heads for work, alone.

Shirley Sebek, still in the hospital, wonders why Gary hasn’t stopped by to see her after work.

Some time between 9:30 and 10 p.m., Janice Holland and Dena Siddens stop by the Sebek home to check on Gary. The home’s light’s are all off and Gary isn’t there, but the kitchen floor has clearly been mopped. The mop and pail are no longer in the bathroom, but near the basement door, and the mop is wet. The basement door is open and the light downstairs is on.

Janice Holland goes into the basement, thinking she’ll find Gary, but he’s not there.

In the living room, the two women notice that two big chairs near the front door have been moved away from their normal positions. Scuff marks — both light and dark colored — mar the floor where the chairs were pulled away.

One of three decorative pillows is missing from the sofa, and the pillow on the right appears to have blood on it. There is a much larger stain — something that also appears to be blood — on the back of the sofa where one’s head would normally rest.

The women leave the duplex to go get their husbands.

The Hollands and Siddens return to the Sebek home and look for the center pillow, which is wider and of a different style than the left and right pillows. The pillow is only important to them because of the blood found on the sofa and another sofa pillow. They contact the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office around 10:30 p.m. to report their findings.

Fremont County Sheriff James E. Findley arrives at the Sebek duplex at 11 p.m., where he takes statements from the Hollands and Siddens. In the kitchen’s breakfast area, Findley finds a doll sitting in a chair, and what appears to be blood specks on the wall above the chair.

Within days, an all-points missing persons bulletin is released to the public, along with Sebek’s physical description.

Wednesday, March 6, 1968

Janice Holland and Dena Siddens go out to Victor Moyer’s rural Hamburg residence between 12:30 and 1 p.m., where they observe Moyer’s car parked in a tin shed. The women look inside the trunk and find the middle section wet with an unknown substance. They also see blood on the right rear bumper and corner of the vehicle, which is consistent with dragging something bloody from the left to the right area. The two woman, now scared, leave Moyer’s property before he returns home.

Fremont County Deputy Sheriff Gary Stephens and Sheriff Findley go to the Victor K. Moyer residence in rural Hamburg, where they observe the substance on the rear fender and bumper of the Moyer car, a 1958 Sunbeam, white over blue over white, model Rapier, license plate number 36-839. They detect other stains on a piece of plastic in the car, on the hand brake handle and steering wheel of the car.

Moyer is asked how blood got on the rear of the car and he states he must have cut his finger. When the officers inquire as to which finger he cut, Moyer retracts his statement, saying he guessed he didn’t cut any finger. Stephens and Findley collect blood scrapings and other evidence from the scene.

Samples of the fabric found in the apartment containing the stains (including the davenport and pillows) and scrapings from the kitchen, along with scrapings and portions of the car containing the stains are taken and sent to the FBI laboratory for analysis.

Gary and Janice Holland visit Shirley at the hospital that evening, and Victor Moyer is there, unusually quiet and visibly nervous. Janice asks her sister about the center pillow on the sofa, and Shirley says it should be there because it’s where she always kept it.

Victor Moyer tells Gary Holland he’s heard “they found blood on the sofa,” and when Holland says officials also found blood on the kitchen wall, the normally talkative Moyer immediately grows silent.

Moyer leaves the hospital without ever having asked Shirley how she and/or the baby are doing.

Results: DNA is not yet a reality in 1968, but the blood collected from both the vehicle and from the fabric in the Sebek home will later be identified as type “A” blood, and Sebek is believed to have type “A” blood. Tests also reveal Moyer has type “O” blood.

March 7, 1968

[Note: Information from Bureau of Criminal Investigation, SYNOPSIS on MISSING PERSON case, GARY EUGENE SEBEK, FILE NUMBER 68424, filed by BCI Special Agent Warren D. Stump, with investigative dates listed as March 6, 7, 8 and 9, 1968. The following excerpts are from Page 12 of the 22-page Synopsis and do NOT include any material listed on Pages 14, 15, and 16, which are stamped CONFIDENTIAL.]

- On March 7, 1968 between the hours of 1:08 P.M., and 1:22 P.M., Sheriff Findley, Deputy Sheriff Ed Collins and the reporting Agent (Warren D. Stump) contacted VICTOR KENNETH MOYER at his Rural Route #2 home in Hamburg, Iowa, to interview Mr. Moyer.

- Deputy Sheriff Collins read the Miranda Warning to Moyer and the interview took place in the sheriff’s vehicle.

- After the Miranda Warning was given to Mr. Moyer, he was asked by Deputy Collins whether or not he understood it, at which time Mr. Moyer stated “yes.”

- Mr. Moyer stated that he wanted to see his attorney, Edwin Gestcher, of Hamburg, Iowa, and stated that Gestcher had called him and wanted to talk with him.

- “It may be noted at this time,” the report says, “that Mr. Moyer went to the court house in Sidney, Iowa and contacted Mr. Gestcher on March 7, 1968 at approximately 11:45 A.M. Mr. Moyer was asked by Deputy Sheriff Ed Collins as to how the blood got on the rear of his car and Mr. Moyer stated that maybe his step-daughter [sic] SHIRLEY SEBEK might know or GARY SEBEK.”

- “The reporting Agent stated that if Mr. Moyer had nothing to do with the possible disappearance of GARY SEBEK, that Mr. MOYER would be willing to take a polygraph test concerning the disappearance of this subject. Mr. MOYER stated that he would be very nervous in taking such a test and would have to consult his attorney first. The reporting Agent stated to Mr. Moyer that compensation regarding his nervousness could be adjusted on the polygraph chart and this would make no difference. Mr. Moyer again refused the test and stated that he would consult his attorney on March 8, 1968 and after a conference with said attorney, would contact the Sheriff’s office in reference to what he could say or could not say.”

- “This was the extent of the conversation that the above officers had with Mr. Moyer. At the time of the questioning by the officials Mr. Moyer appeared to be very nervous.”

March 11, 1968

Dorothy Simpson, the Sebeks’ neighbor who lived at 1606 Main Street in Hamburg, told Deputy Sheriff Stephens that on the night of March 4, 1968, she’d heard two shots fired around 11:30 p.m. She said she waited five to 10 minutes before looking outside, and saw that all the lights were on in the Sebek home. She told her husband about having heard the shots, but he said the sounds probably came from a backfiring car.

Simpson told Deputy Stephens she was “definite” about it being shots fired and not any vehicle backfiring.

Thursday, March 21, 1968

A Hamburg Reporter article publishes comments by Fremont County Sheriff Jim Findley stating there are no new developments in Sebek’s disappearance. The article says that Findley’s office — along with state law enforcement officials — checked out several pieces of information during the previous week, but failed to turn up any clues or anything of substantial nature.

The newspaper also reports:

A davenport in the Sebek cottage at the Dave Ware Apartments on Main Street was removed for further study of possible blood stains by Sheriff Findley and has not yet been returned, according to Mrs. Ware. She says to her knowledge the cottage is still under jurisdiction of the sheriff’s office, and no one has moved into or out of it.

Mrs. Sebek and newborn son, Patrick, stay with friends in Hamburg while waiting for officials to release the cottage to Mrs. Sebek.

Gary Sebek’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Charles Sebek, along with Gary’s wife Shirley, tell the press they do not think Gary “just went off somewhere.”

April 24, 1968

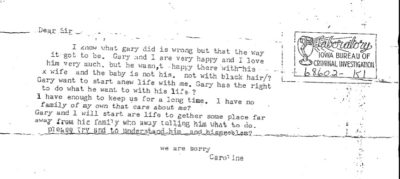

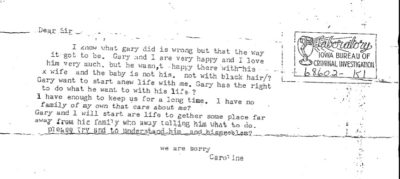

A typewritten note and envelope, bearing a post mark of Hiawatha, Kansas, is mailed to Shirley Moyer Sebek, purportedly written by a woman named “Caroline,” stating that she and Gary had run off together because Gary was not happy with his wife and family.

Courtesy Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation (now DCI)After obtaining a search warrant for any typewriters belonging to Victor K. Moyer, Iowa BCI experts confirmed this April 24, 1968 letter written to Shirley Sebek by a purported “Caroline” was in fact written by Victor Moyer on his personal typewriter.

The writer of the letter also falsely accuses Gary and Shirley Sebeks’ newborn son as not belonging to Gary because the child has “black hair.”

May 10, 1968

A search warrant dated May 10, 1968, addresses a number of letters, both typed and handwritten, at times addressed to Shirley Sebek and other times addressed to Gary Sebek, used as a means of accomplishing and concealing a felony in attempts to mislead the BCI’s investigation into Gary Sebek’s disappearance.

The Bureau of Criminal Investigation would later match the handwritten letters with Victor Moyer’s handwriting and also match the typewritten letters to a typewriter owned by Victor Moyer.

May 13, 1968

On May 13, 1968, Shirley Sebek voluntarily submits to two polygraph tests, both of which are administered by Robert L. Voss, polygraph examiner for the Iowa BCI (official report on file).

Voss’s report on the polygraph results, submitted to BCI Director R.D. Blair and Fremont County Sheriff James Findley, concludes that Shirley Sebek passed both tests with no attempts to deceive, and state she is not withholding any information pertinent to the investigation concerning her husband’s disappearance.

The report reflects Mrs. Sebek’s belief that her husband is deceased and her belief that her father, Victor Moyer, is responsible for his death. Mrs. Sebek also expresses her own fear of Victor Moyer and her willingness to cooperate with authorities in any way.

Thursday, January 16, 1969

The Hamburg Reporter publishes an article — “FBI Enters Search for Gary Sebek” — stating the 20-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Sebek is now being investigated by the FBI for failure to answer a draft board summons. Inquiries were made by the Bureau at Rock Port, where Sebek was registered for the draft.

The newspaper states:

[Sebek’s] name will go on the list of persons sought in connection with possible draft evasion, and the search for him will automatically become nationwide.

The newspaper says clues as to what actually happened are more likely to be turned up by the FBI than “through the limited facilities of local and state law officers.”

Friday, April 11, 1969

Courtesy photo The Hamburg Reporter

Courtesy photo The Hamburg ReporterOn Friday, April 11, 1969, more than 40 area law officers and volunteers searched 240 acres of ground farmed by Victor Moyer as they sought clues to the whereabouts of Moyer’s son-in-law, Gary Sebek. Sheriff Ed Collins led the search under the direction of James P. Tighe, district agent for the Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation.

Forty law enforcement officials, armed with post hole diggers, shovels, probes, and a mine detector, execute a search warrant for the 240 acres of land Victor Moyer farms northwest of Hamburg.

The search is conducted under the direction of James P. Tighe, district agent for the Iowa Bureau of Criminal Investigation, and Fremont County Sheriff Ed Collins.

Thursday, April 17, 1969

In a story published by the Hamburg Reporter, Sheriff Collins says the “thorough search of ground farmed by Victor Moyer was done to quiet some rumors, and to check out certain aspects of the disappearance not done previously.”

The Reporter cites once again Sebek’s visit to the Nebraska City, Neb., hospital on March 4, 1968, where his wife had given birth to a child, and Sebek’s subsequent return to Hamburg later that day. “No clue,” the paper reports, “has been found as to his whereabouts since he was last seen by friends at his Hamburg apartment.”

The page one story — which contained no byline — also states:

The investigation languished through a political campaign during which Deputy Collins resigned to run for sheriff, winning over Sheriff Jim Findley, and then winning the general election last fall.

Interest in the case surfaced again early this year when the FBI started searching for Sebek when he failed to appear for a draft physical. Results of their work is not known, but the usual procedure is for the FBI to, among other things, start the massive fingerprint comparing process in motion.

The article references a conversation with Sheriff Collins from Monday, April 14, 1969, where Collins tells the paper his office has been sifting information for some time. Collins will not speculate whether Friday’s ground search was based on new evidence.

The Hamburg Reporter also quotes County Attorney Gene Eaton as saying “the case is still under active scrutiny and will continue to be under regular investigation.”

Before the year ends, the city of Hamburg purchases (unrelated) land for the city’s cemetery.

November 16, 1974

Melvin Price, a 26-year-old US Navy and Vietnam veteran — is driving from his Lincoln, Neb., home through Hamburg at 6:30 p.m. when he comes to a barricade at the west ditch bridge. Not knowing construction workers are still laying cement after dark on the I-29 access near Hamburg’s city limits, Price maneuvers his car around the barricades and quickly becomes stuck in wet concrete.

The construction company contacts authorities, but when the company’s contractor declines to file charges, Price is let go.

Price drives into Hamburg and goes to the VFW Club, where he visits with Victor Moyer and Shirley’s younger sister, Janice. Someone later sees Price kissing Janice.

Even though Moyer had only adopted siblings John and Shirley and not their youngest sibling, Janice, Price didn’t know any better about getting too close to the family of girls and women Moyer attempted to control, one of Sebek’s relatives told Iowa Cold Cases. (Names on file and available to state and federal investigators.)

Moyer’s flaunting obsession with Shirley caused undue emotional stress on his wife, Ruth Marie (Nahkunst), family members said, and on March 13, 1968, Sheriff Findley said he discovered Mrs. Moyer was “voluntarily admitted” to the Clarinda Mental Health Institute on March 27, 1965, and discharged May 13, 1965, as “recovered.”

November 17, 1974

Melvin Price is seen leaving the VFW Club with some companions around 1:30 a.m.

At 4:30 a.m., a passing Farragut trucker finds Price’s dead body lying along Iowa Highway 42 about one mile west of Riverton. A witness report says Price appeared to have been beaten in the head with a crowbar.

Autopsy results from Jenny Edmundson Hospital in Council Bluffs list Melvin Price’s cause of death as blunt force trauma to the head. Manner of death is cited as Unknown, but (likely given the location where the trucker found the body) then listed as a “probable hit-and-run” even though Price suffered no broken bones consistent with hit-and-run vehicular homicides.

Fremont County Sheriff Bob Jenkins and Iowa BCI agents investigate the case, which, like that of Gary Sebek, eventually goes cold.

New Grave Uncovers Old Bones

On February 16, 2012 — more than four decades after Gary Sebek disappeared — excavation workers digging a new grave unearth a skeleton in the Hamburg Cemetery. While many hope it might be Sebek’s remains so his family can finally have closure, speculations are put to rest when the Iowa State Archaeologist Office reports the remains — those of a male of European ancestry between age 16 and 23 — were buried sometime between 1850 and the early 1900s.

Gary Sebek’s body has never been found.

Gary’s parents — married two weeks shy of 66 years — died within 2-1/2 months of each other in 2008; Ruth Ella passed away February 10, with Charles, 87, following on April 19.

Shirley Ann (Moyer) Sebek died Tuesday, Aug. 18, 2009 at the Westwood Hills Health Care Center in Popular Bluff, Missouri. She was 62 years old.

Victor Moyer took any known secrets to the grave when he died July 24, 2014, at age 94.

Courtesy photo Sandy Thompson from findagrave.com

Courtesy photo Sandy Thompson from findagrave.comGary Sebek’s gravestone is next to his parents’ stone in High Creek Cemetery in Rock Port, Missouri.

About Gary Sebek

Gary Eugene Sebek was born December 29, 1947, to Charles and Ruth Ella (Pierson) Sebek.

A gravestone erected in his memory was placed in High Creek Cemetery in Rock Port, Missouri, in Atchison County.

In addition to his parents, Gary was survived by his wife, Shirley (Moyer) Sebek; a daughter, Lisa Ann Sebek; a son, Patrick Sebek; a sister, Denese Sebek; brother-in-law John Moyer and John’s wife Monica.

Monica Moyer died July 10, 1998, at age 44.

Gary’s gravestone — which lists his date of death as the same month he went missing — rests next to his parents’ stone.

Information Needed

If you have any information about Gary Sebek’s unsolved disappearance/murder or any known accomplices who helped dispose of Sebek’s body, please contact the Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation at (515) 725-6010 or email dciinfo@dps.state.ia.us. You may also contact the Fremont County Sheriff’s Office at (712) 374-2424, or the FBI at (402) 493-8688 or email Omaha@ic.fbi.gov.

Sources:

- Fremont County Sheriff’s Office

- Iowa Division of Criminal Investigation (formerly the Iowa BCI)

- Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Personal correspondence with Gary Sebek’s family members (ongoing)

- Personal correspondence with acquaintances of Gary Sebek (names on file and available to current investigating agencies)

- Victor K. “Buck” Moyer Obituary, bigappleradio.am, July 24, 2014

- Victor Kenneth “Buck” Moyer (1920 – 2014) — Find a Grave Memorial

- Victor (Buck) Moyer Obituary — Rash-Gude Funeral Home, July 24, 2014

- “Skeletal remains pre-date missing Hamburg man,” The Hamburg Reporter, March 5, 2012

- “Skeletal remains found in Hamburg; possible connection to 43-year-old case being investigated,” The Hamburg Reporter, Feb. 20, 2012

- Shirley Ann Moyer Sebek (1947 – 2009) — Find a Grave Memorial

- Ruth Marie Nahkunst Moyer (1923 – 2002) — Find a Grave Memorial

- “Day-long farm ground search reveals no Gary Sebek clues,” The Hamburg Reporter, Thursday, April 17, 1969

- “FBI Enters Search for Gary Sebek,” The Hamburg Reporter, January 16, 1969

- Gary Eugene Sebek (1947 – 1968) – Find A Grave Memorial

- POLYGRAPH EXAMINATION OF: Shirley Ann Sebeck [sic], to include Arrangements, Procedure, Results, and Conclusion, by Robert L. Voss, Polygraph Examiner, dated May 13, 1968

- “INFORMATION FOR SEARCH WARRANT, STATE OF IOWA, Plaintiff, vs. ANY TYPEWRITER(S) SEIZED, Defendant, In the District Court of the State of Iowa in and for Fremont County, May 10, 1968

- State of Iowa, BUREAU OF CRIMINAL INVESTIGATION, Department of Public Safety, Supplementary Report by Warren D. Stump, Special Agent, dated April 8, 1968

- FBI Laboratory, letter to Iowa BCI Director R.D. Blair, Attention Mr. Andrew M. Newquist, Special Agent, from J. Edgar Hoover regarding evidence received March 15, 1968, to include Q1: Smear from right side of rear bumper; Q2: Smear from right side of rear fender; Q3: Smear from chrome strip; Q4: Smear from left doorjamb area; Q5: Section of plastic; Q6: hand brake handle; Q7: Steering wheel; Q8: Fabric; Q9: Pillow, submitted for chemical analyses, Airmail letter dated April 5, 1968

- “Gary Sebek is still missing,” The Hamburg Reporter, March 21, 1968

- State of Iowa, Bureau of Criminal Investigation, Department of Public Safety, 22-page Synopsis made by Warren D. Stump, Special Agent (CONFIDENTIAL stamped on pages 14, 15, and 16) regarding the investigation of missing person GARY EUGENE SEBEK, with Investigation Dates listed as MARCH 6, 7, 8 & 9, 1968, and the Synopsis dated March 18, 1968.

- “Teletype — Physical Evidence and RESULT OF EXAMINATION,” by R. D. Blair, Director, Bureau of Criminal Investigation, dated March 11, 1968

- State of Iowa, Department of Public Safety letter from Bureau of Criminal Investigation Director R.D. Blair to J. Edgar Hoover, Director, Federal Bureau of Investigation, dated March 8, 1968

Copyright © 2024 Iowa Cold Cases, Inc. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Hamburg in Fremont County

Hamburg in Fremont County

It was clearly the father in law!

GROSSS!

How disgusting!!

They are all passed away now.

I hope there is piece for Gary & his wife now.

Fiction makes for great reading material and some of this story is pure bullshit made up by people wanting to add to the story how many decades later?? Your not a fact checker you make your own opinions and listen to hearsay without any responsible reporting, because I would love nothing more than to see a copy of my dad’s non existent suicide letter, and I’m sure his suicide had nothing to do with his mental illness or my parents separation. Funny I was told 3 years ago that my dad went to Kenny’s house but he wasn’t home, now it’s he went to his job? Let’s at least keep it consistent. This really is the lowest that people can stoop to talk about someone who has been dead for so long and to let his children read that he wrote a suicide note because of something that happened 20 years before he died, because not one person in my family has ever seen this alleged note. This is disgusting.

Kim Gill, I am so sorry that, your Dad, was put into this article. It is bad enough, that one family, had to suffers though this. Then to add another family with no prove of a letter! I went to school with your dad. I was back in town shortly, after his death. My Grandmother told me about it and she said Gordon, mother had been worried about him because he had be so depressed and recently been separated from his wife. I too, as many do suffer from mental illness, it is a hard thing to ask for help for, and a hard thing to treat. I hope you learn not to let the fool out there hurt. No one know your Dad like you and yours. He was a good person. And nothing anyone can say can hurt him now. So don’t let it hurt you. God Bless you and your family.

My father sheriff Ed Collins believed Moyer did it, but couldn’t prove it.. I saw the couch was really bloodstained.

David, your father, of course, was correct.

This is very sad and very sickening!

Fascinating. Never heard this one before. Iowa just keeps leaking its darker side.

As a homegrown Iowan, from the “streets” of Waterloo, I have always maintained. … thugs…. not a problem, Piss off a farmer and you are going to disappear.

Laura, very very true. I’m sure you’re all-too-aware of the Adam Lack and Gary Lack unsolved murders.

So true!

So sad and sick!!!!

So sad

Why hasn’t Gary Holland told what he knows?

I have to agree, it sound like the father -in-law.

What a mess they made in the investigation of this case, sounds like it was his father-in-law.

yeah I heard this story too when I was a kid, I was in the hospital with Victor Moyers wife and she was talking about it. I was scared and my parents didn’t have a phone so I called my brother and Lois Lynn so I would have someone to talk to because I was scared. The nurses then came into my room and took the phone out of my room because It was late night and I guess I was bothering people by being on the phone. His wife told me that they were searching their land because they thought that her husband had chopped the son in law up in pieces and distributed him by airplane over his land and then plowed it under. I was only 9 and I didn’t want to hear that stuff.

Wow!

I bet you he did do that though!