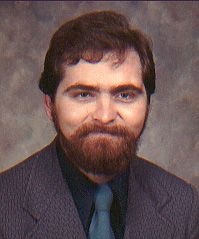

Neal Townsend

Neal Robert Townsend

Homicide

Neal Robert Townsend

Age: 29

Lifelong Anamosa, Iowa, resident (Jones County)

Died at Alola Apartments

Lava Hot Springs, Idaho

Bannock County, Idaho

Investigating Agency: Bannock County Sheriff’s Office

End of Watch: Tuesday, Sept. 2, 1975

Case Summary compiled by Jody Ewing

Note: Though Neal Townsend died in Lava Hot Springs, Idaho, his staged suicide/homicide is included here on Iowa Cold Cases under those we call “Still Ours.”

Neal Robert Townsend grew up and spent most of his life in Anamosa, Iowa. He worked with various industries in the city trying to help people with alcohol problems, and graduated in November 1973 from the in-service training program at University of Iowa Alcoholism Center at Oakdale. In January 1974, he began working full-time at the Citizen’s Committee, an organization for whom he’d previously worked half days as an industrial counselor.

Courtesy Cedar Rapids Gazette, July 22, 1973

Courtesy Cedar Rapids Gazette, July 22, 1973A Cedar Rapids Gazette article applauds Neal Townsend for his commitment to educating alcoholics.

His task was to educate supervisors and foremen about the first and second stages of alcoholism so they could identify and work with employees before it was too late, the Cedar Rapids Gazette wrote about Townsend’s commitment to public service in an article dated Sunday, July 22, 1973.

“Someone helped me and I want to return the favor,” the 27-year-old Townsend told the Gazette.

Townsend already had made a phenomenal difference in Iowa; in 1972, the Citizen’s Committee had referred 179 industrial workers, and only three of them, after counseling, lost their jobs. Just 50 had been referred by 1973, and Townsend fought hard to help the person overcome his or her alcoholism problem and keep his or her job.

In late June, 1975, he spoke with former Cedar Rapids police officer Thomas “Tom” Childs, a close friend who’d recently moved to Idaho to work for the Pocatello Police Department. Childs’ family remained in Iowa, but said things were heating up in Idaho as the FBI’s massive, agent-intensive manhunt for Patty Hearst moved into western states.

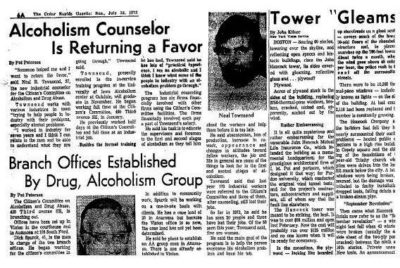

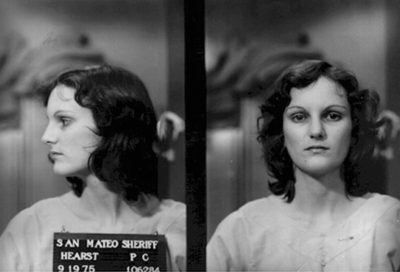

Courtesy wikimedia.org

Courtesy wikimedia.orgPatricia “Patty” Hearst’s booking photo after being captured Sept. 18, 1975, in San Francisco.

Hearst, the granddaughter of publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst, had been kidnapped from her Berkeley, California apartment more than a year earlier on Feb. 4, 1974 by the urban guerrilla group, the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA).

The SLA, led by hardened criminal Donald DeFreeze, wanted to incite a guerrilla war against the U.S. government and destroy what they called the “capitalist state.” When Los Angeles police surrounded an SLA safe house on May 17, 1975, a massive shootout ensued as the building went up in flames. DeFreeze was one of six SLA members killed in the fire, but Hearst remained at large, along with other members on the run in the West.

The idea of being involved with the Patty Hearst case enticed Townsend to give up his Iowa job, and in early July 1975 he went to work as an officer for the Lava Hot Springs Police Department in Bannock County, Idaho. He, like Childs, left his family behind in Iowa while waiting to see how things worked out.

On September 2, 1975 — just 16 days before FBI agents captured Patty Hearst in San Francisco — Townsend would be shot dead with the second .38 caliber pistol issued to him by local police. Officials quietly ruled his death a suicide as tensions between Lava Hot Springs police and the Bannock County Sheriff’s Department reached the boiling point and spilled over into the southeastern county and into district court.

Public Corruption

Townsend, who worked under Police Chief John Burris, found things were not as they seemed in the small Idaho community.

Police routinely confiscated what they believed to be “controlled substances” (marijuana), while some of those very officers grew and sold their own illegal marijuana. The disillusioned Townsend frowned upon the clandestine activities, and let close family back in Iowa know what was being hidden in plain sight.

At approximately 1:30 a.m. on Tuesday, September 2, 1975 — just two months after Townsend joined the police force — Bannock County deputies arrived at his apartment, and subsequently announced Townsend had shot himself (in the stomach) with a .38 revolver.

The police department had already begun investigating the alleged “suicide” before any deputies called it in. Local officials bypassed standard operating procedures and conducted no investigation. They never contacted the county medical examiner to request an autopsy, which never got done.

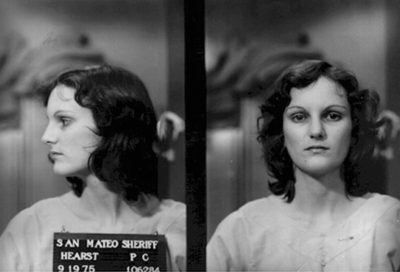

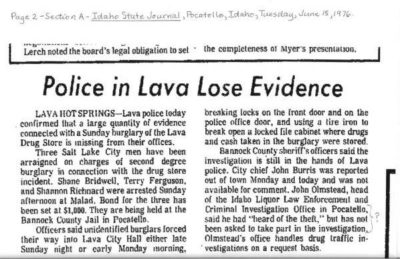

From the Idaho State Journal, June 15, 1976

Not long after Townsend’s body arrived back in Iowa for burial, secrets within the Lava Hot Springs Police Department were spilling across pages of witness statements …not over what happened to Townsend, but rather over what had happened to the alleged “suicide” gun Townsend supposedly used to shoot himself in the abdomen and what had happened to other evidence.

The Iowa native would already be buried in Anamosa’s Riverside Cemetery by the time Lava Hot Springs Police Chief John C. Burris landed in court — charged with embezzlement by a public officer and selling handguns belonging to the city. As the list of charges accrued, Lava Hot Springs and Bannock County residents questioned for the first time what had happened to the friendly new officer from Iowa who’d come all the way from Iowa to serve their small community.

They’d barely got the chance to meet or know him.

Back in Iowa, Townsend’s family never believed for a moment he’d committed suicide. Their own search for answers took them from local inquiries to the county and state and gubernatorial level, and from the FBI and US Department of Justice to US President Bill Clinton.

The answer proved more elusive than what happened to Patty Hearst.

Controversy surrounds “suicide weapon”

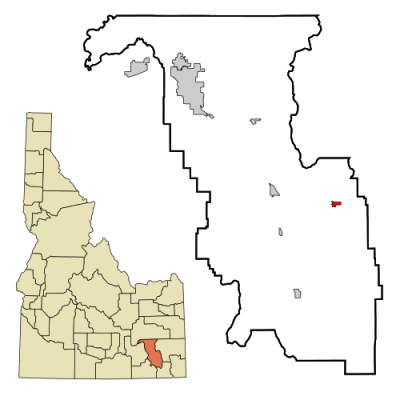

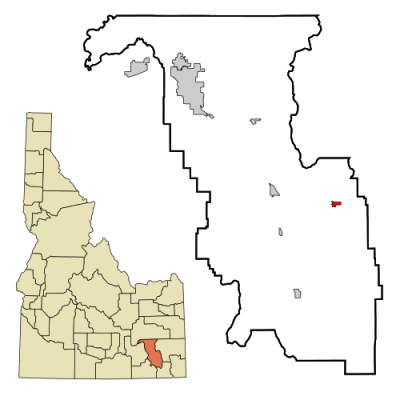

Lava Hot Springs in Bannock County, Idaho

When Neal Townsend first joined the Lava Hot Springs Police Department in July 1975, the city authorized him credit to purchase police equipment, including a Colt .38 caliber pistol, Serial No. 799581. Under the arrangement — commonly utilized by the city and its officers to purchase “personal belongings” — Townsend was to reimburse the city in installment payments for the cost of the equipment.

Townsend’s total bill for police equipment, including $70 for the pistol, came to $145.80. When Townsend said he’d lost the pistol in the Portneuf River while on duty, the city authorized the purchase of a replacement handgun.

Townsend bought another .38 caliber Colt revolver, Serial No. 911067, for $75 on July 29, 1975, using his credit account with the city.

The gun, which should have been kept for evidence, turned up missing, but its whereabouts finally became known in the State vs. Burris trial in 1977.

STATE v. BURRIS

NO. 13090.

619 P.2d 1136 (1980)

101 Idaho 683

STATE of Idaho, Plaintiff-Respondent, v. John C. BURRIS, Defendant-Appellant.

Supreme Court of Idaho.

Rehearing Denied December 15, 1980.

R.M. Whittier of Whittier & Souza, P.A., Pocatello, for defendant-appellant.

David H. Leroy, Atty. Gen., Lynn E. Thomas, Deputy Atty. Gen., Boise, for plaintiff-respondent.

BAKES, Justice.

Defendant John Burris was the police chief of Lava Hot Springs from May 1, 1974, until August 31, 1976. During his tenure, defendant had possession of a number [619 P.2d 1137] of firearms, some of which belonged to the city of Lava Hot Springs.

On June 24, 1977, defendant was charged in a single count complaint (Case No. C-2064) with embezzlement by a public officer. I.C. § 18-2402. The complaint alleged that defendant sold a Smith & Wesson Eastfield model shotgun belonging to the city and appropriated the proceeds of the sale to his own use. Defendant was bound over on that charge after a preliminary hearing held on July 12, 1977. On July 20, 1977, the prosecuting attorney filed an information reiterating the allegations of the complaint.

On August 22, 1977, the prosecuting attorney filed a second three-count complaint (Case No. C-2120) again charging the defendant with embezzlement by a public officer. This complaint alleged that defendant misappropriated three Colt .38 caliber pistols belonging to the city. The serial numbers of the pistols were as follows: 922948 (Count I), 799581 (Count II), and 911067 (Count III). The preliminary hearing was held on October 26, 1977, and the defendant was bound over on all three counts.

On November 2, 1977, the prosecuting attorney filed a three-count information which reiterated the allegations of the complaint.

On July 9, 1978, Count II of the second information was dismissed on motion of the prosecution “in the interest of justice.”

The two informations were consolidated for trial. On January 13, 1978, the jury found defendant guilty on all the remaining counts. On appeal, the defendant asserts that the evidence is insufficient to sustain the jury’s verdict. We disagree and affirm the defendant’s judgment of conviction on all three counts.

The evidence adduced at trial was conflicting and sharply disputed. It will be necessary to discuss the evidence in detail, tracing the history of each of the three firearms which are the subject of the charges. The applicable law is, by comparison, straightforward and requires only brief discussion.

Defendant was charged with a violation of I.C. § 18-2402. That section provides that “[e]very officer … of any … municipal corporation … who fraudulently appropriates to any use or purpose not in the due and lawful execution of his trust, any property which he has in his possession or under his control by virtue of his trust … is guilty of embezzlement.”

The scope of our appellate review is well established. “The function of an appellate court is to examine the record to determine if competent and substantial evidence exists to support the verdict… . Where there is such evidence, the verdict will not be disturbed on appeal… . Further, the court is not authorized to substitute its judgment as to the credibility of the witnesses and the weight to be given their testimony by the jury.” State v. Warden, 100 Idaho 21, 23, 592 P.2d 836, 838 (1979) (citations omitted). Applying these principles to the record in this case, we conclude that the evidence does sustain the defendant’s conviction on all three counts.

I. COUNT I OF CASE NO. C-2064: THE EASTFIELD SHOTGUN.

In January of 1975, the defendant purchased a Smith & Wesson Eastfield [619 P.2d 1138] model shotgun for the Lava Hot Springs police department. Defendant concedes that the shotgun was the property of the city. Defendant sold the weapon to a private citizen in June of 1975 for $80. Defendant testified that he sold the shotgun with the knowledge and approval of Police Commissioner A.D. Potter. Defendant claimed he sold the weapon because it would not fit in the gunrack of the patrol car. Defendant further testified that he took the $80 in proceeds and purchased a replacement shotgun, a Browning automatic, from a friend named Terry Hoadley. Defendant stated that approximately two weeks after purchasing the Browning, he attempted to fire it, only to discover that it was inoperative. Defendant testified that he then took the Browning to David Christensen in July of 1975 to have it repaired. Christensen never repaired it. In fact, he retained possession of it until October of 1977.

Defendant was fired in August of 1976. He testified that he was asked to return the city’s shotgun at that time and therefore purchased a Savage shotgun “to replace the shotgun that was broken.” The Savage was purchased by defendant on credit on September 1, 1976, and turned over to the Lava Hot Springs police department. The defendant paid for the Savage shotgun with his own funds.

There were sharp conflicts between the testimony of the defendant and the testimony of other witnesses. Both Mayor Campbell and Police Commissioner Potter denied authorizing the sale of the Eastfield shotgun. They also testified that they were wholly unaware of the purchase of the Browning shotgun.

Defendant claims to have purchased the Browning after having sold the Eastfield in June of 1975. However, Hoadley testified that he sold the Browning shotgun to defendant in March or April of 1975. Christensen stated that he thought the defendant purchased the Browning in May of 1975. If the jury believed the testimony of Campbell, Potter, Hoadley and Christensen, the defendant’s claim that he purchased the Browning as a replacement for the Eastfield would be shattered.

Defendant’s trial testimony also conflicted with the statement he had made to county and federal investigators on November 7, 1976. In that statement, defendant claimed to have sold the Eastfield in September or October of 1975, and replaced it with the Savage shotgun in November or December of 1975. He further stated that he took the Savage to Christensen to have the barrel cut down to fit in the gunrack; that Christensen kept the gun for about four months; and that the defendant “got it back from him when I resigned in August of 1976, and returned it to” a Lava Hot Springs police officer.

Given these inconsistencies and conflicts, the jury was entitled to believe that the defendant sold the Eastfield intending to retain the proceeds; that he was not authorized to sell it; that he had purchased the inoperative Browning before he sold the Eastfield and therefore could not have intended the Browning to be a replacement shotgun; and that defendant’s purchase of the Savage shotgun (over a year after the sale of the Eastfield) was prompted only by the mayor’s demand that he return the city’s shotgun. We hold therefore that there is sufficient evidence to sustain the conviction on Count I of Case No. C-2064.

II. COUNT I OF CASE NO. 2120: SMITH & WESSON REVOLVER, SERIAL NO. 249320, THE “SNOW PISTOL.”

In 1967, an officer named Doug Snow retired from the Lava Hot Springs police department. Upon his retirement, the city paid him $100 for some police equipment, which included a pearl-handled.38 caliber revolver. Thereafter, the weapon was carried by Officer Bronson, who testified that he was issued the weapon as “city equipment” at the commencement of his employment. Bronson stated that he returned the weapon to one of defendant’s deputies upon leaving the force. State’s Exhibit E is a Smith & Wesson pearl-handled revolver, Serial No. 249320. Bronson identified Exhibit E as the weapon he carried during his tenure. [619 P.2d 1139]

David Copeland, a private citizen, testified that he purchased a pearl-handled revolver from the defendant for $50 in January of 1975. Copeland said that he had sold the gun to his father-in-law approximately two days later. In September of 1977, at the request of the prosecution, Copeland retrieved the revolver from his father-in-law and turned it in to Russell Edwards, the current police chief of Lava Hot Springs. The testimony of Copeland, his father-in-law and Edwards firmly established that the revolver in question, which Copeland purchased from the defendant, was a pearl-handled Smith & Wesson revolver, Serial No. 249320.

Defendant’s testimony again is in conflict with the state’s evidence. Defendant admitted selling a pearl-handled revolver to Copeland. He also admitted that the weapon he sold did belong to the city and was carried by Officer Bronson, but insisted that the weapon he sold was not State’s Exhibit E (the weapon charged in Count I), but was instead a Colt. In fact, defendant claimed that Exhibit E, the pearl-handled Smith & Wesson, was never in his possession. Defendant also testified that the sale was authorized by then Mayor Seppi. Seppi denied ever giving defendant permission to sell “the old pearl-handled .38 caliber revolver.” Finally, defendant testified that he used the proceeds from the Copeland sale to purchase the Eastfield shotgun.

Again, defendant’s story was directly contradicted by evidence introduced and testimony elicited by the state. The jury was consequently entitled to disbelieve defendant’s version of the facts. We affirm defendant’s conviction on this count also.

III. COUNT III, CASE NO. 2120: COLT PISTOL, SERIAL NO. 911067, THE “TOWNSEND SUICIDE” PISTOL.

In July of 1973, the city of Lava Hot Springs authorized one of its police officers, Neal Townsend, to use the city’s credit to purchase police equipment, including a Colt .38 caliber pistol, Serial No. 799581. Under the arrangement, which was often utilized by the city and its officers, Townsend was to reimburse the city for the cost of the equipment. According to then Mayor Campbell, items purchased under this arrangement were Officer Townsend’s “personal” belongings.

The bill for Townsend’s police equipment came to $145.80, $70 of which was for the pistol. Soon after the equipment was purchased, Townsend lost the pistol in the Portneuf River.2 The city authorized the purchase of a replacement handgun. On July 29, 1975, Townsend purchased another .38 caliber Colt, Serial No. 911067, again using the city’s credit. The cost of the second pistol was $75.

Townsend made two $30 payments to the city in July and August of 1975. On August 14, 1975, the city paid the $145.80 bill for Townsend’s first purchase of police equipment. In early September, Townsend purportedly committed suicide with the second pistol. The city paid for that weapon on September 11, 1975. The suicide weapon was turned over to the Bannock County authorities who were investigating Townsend’s death. On September 29, 1975, the suicide pistol was returned to the defendant. Another police officer testified that defendant told him at that time that the pistol would not be returned to the Townsend family with his personal effects because it was the property of the city.

The defendant acknowledges receipt of the pistol from Bannock County investigators, but insists that the pistol “came up missing” from his office. However, Terry Hoadley testified that he purchased a Colt .38 caliber pistol from defendant in the fall of 1975 and sold the weapon soon thereafter to a Californian visiting Idaho on a hunting trip. The latter individual returned the pistol to the prosecution. At trial, that pistol was identified as a Colt .38 caliber handgun, Serial No. 911067, the very same weapon Townsend had purchased after he lost his first pistol in the river. We again observe that the defendant’s testimony is diametrically opposed to other evidence in the record. It is the jury’s function to assess the credibility of witnesses and resolve conflicts in the record, and we will not disturb the jury’s verdict where supported by substantial evidence.

Defendant contends, however, that his conviction on Count III should be reversed because the state failed to prove that the city owned the Townsend suicide pistol.3 Defendant contends that Townsend was the true owner of the pistol, relying on a U.C.C. provision, I.C. § 28-2-401(2), which states that, unless otherwise explicitly agreed, title passes to the buyer upon completion of physical delivery.4 According to defendant, the city was merely a creditor. There is unquestionably support in the record for the defendant’s theory. There is also evidence to the contrary.

The vendor’s receipt for the pistol stated that it was sold to the Lava Hot Springs police department. The proprietor of the gun shop testified that in his mind the sale was being made to the city police department. No sales tax was imposed upon the sale, since the city was considered to be the purchaser. See Idaho Const. art. 7, § 4; I.C. § 63-105A. Although Officer Townsend had made a total of $60 in payments toward the purchase of the first pistol and other police equipment, he had made no payments on the second pistol.

Although Mayor Campbell did at one point testify that he considered the pistols to be Townsend’s “personal” property, he later testified that he considered the second pistol to be the property of the city. Finally, the defendant himself, after receiving the alleged suicide pistol from county authorities, told a fellow officer that the handgun would not be returned to Townsend’s family because it was the property of the city.

The jury was properly and accurately instructed regarding the applicable U.C.C. provision cited by defendant in support of his theory. While the nature of the purchasing arrangement between the city and Officer Townsend was disputed, there was substantial evidence upon which the jury could conclude either that (1) the city was the original purchaser of the pistol and retained title throughout the course of this controversy or (2) that Townsend was the original owner, but that title reverted to the city upon Townsend’s tragic failure to make any payments whatsoever on the second pistol. See State v. Jesser, 95 Idaho 43, 501 P.2d 727 (1972).

[619 P.2d 1141]

The evidence was sufficient to sustain the conviction and the judgment below is affirmed.

DONALDSON, C.J., and SHEPARD, McFADDEN and BISTLINE, JJ., concur.

FOOTNOTES

1. Originally Count I of the complaint made before the magistrate charged the defendant with embezzling a Colt pistol, Serial No. 922948. The record indicates that Count I of the complaint was amended by interlineation to indicate that the weapon embezzled was a Smith & Wesson pistol. This latter weapon, Serial No. 249320, was the weapon described in Count I of the information filed with the district court. The defendant, in one of his assignments of error, asserts that the court “erred in permitting the State to amend the information changing the charge on Count I in criminal case 2120 by striking the word Colt and inserting the words Smith & Wesson” and also by changing the serial numbers. However, the information filed in the district court was never amended. It was the complaint before the magistrate which was amended. Furthermore, the defendant does not support this alleged error with any argument or authority in his brief. Even if the magistrate erred in permitting Count I of the criminal complaint to be amended, the failure to support the alleged assignment of error with argument and authority is deemed a waiver of the assignment. E.g., Voyles v. City of Nampa, 97 Idaho 597, 548 P.2d 1217 (1976); I.A.R. 35(a)(6).

2. The lost pistol was later recovered and sold by the defendant. Although defendant was originally charged with embezzling that pistol in Count II of Case No. C-2120, the charges were dropped on motion of the prosecution. There was considerable confusion at oral argument concerning which Townsend pistol was the subject of the remaining charge, Count III of Case No. C-2120. The record clearly reflects that it was not the pistol lost in the river, but was instead the replacement pistol, with which Officer Townsend allegedly committed suicide.

3. Both the defendant and the state seem to agree that the state needed to prove that the city was the owner of the allegedly embezzled property. While it is true that the state did plead that fact in its information, it seems clear from a reading of the embezzlement statute that the embezzled property need not belong to the entity for which the defendant is an officer. I.C. § 18-2402 requires only that the defendant misappropriate “any property which he has in his possession or under his control by virtue of his trust.” Thus, the custodian of an evidence locker may be found guilty of embezzlement by a public officer if he misappropriates evidence belonging to private citizens entrusted to his care for use in criminal prosecutions. By the same token, proof that the suicide pistol belonged either to Townsend or the city would support a conviction under I.C. § 18-2402. Under any version of the facts, it was clear that the pistol did not belong to the defendant. As we have noted, however, the state did allege in the information that the pistol belonged to the city. Since we affirm the jury’s verdict on Count III of Case No. C-2120 on other grounds, we need not resolve the issue of whether proof of ownership by Townsend would have constituted a fatal variance from the facts as alleged in the information. See State v. Whitlock, 82 Idaho 540, 356 P.2d 492 (1960).

4. The defendant’s theory of the case places considerable emphasis on the location of title. The U.C.C. has firmly rejected the concept of title as the dispositive factor in determining the rights and obligations of parties to personal property. I.C. §§ 28-2-401 and 28-9-202.

Daughter pursues case all the way to White House

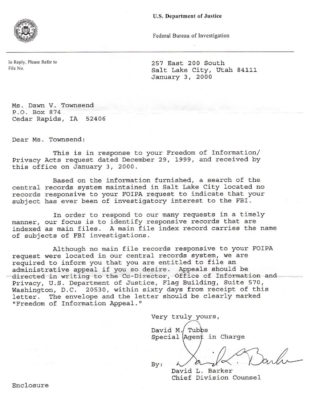

Letter to Dawn Townsend from FBI/US Department of Justice David L. Barker, January 3, 2000

Shortly after his death, Neal’s daughter, Dawn V. Townsend, began what became a very long journey through local and state agencies before eventually sending an email to President Bill Clinton on December 26, 1999. The White House forwarded copies of the letter to the US Department of Justice and the FBI.

Dawn’s daughter, Amanda Wagner, told Iowa Cold Cases she grew up watching her mother’s endless quest to get any kind of answer from anyone.

“Though his death was ruled a suicide, too many things and unanswered questions point in another direction,” Wagner told Iowa Cold Cases in October 2015.

Her mother even created a Facebook page titled, Neal Townsend What Happened?

At every governmental level, Dawn Townsend got ambiguous answers, excuses, and she read through many altered and redacted reports. In certain instances, officials outright denied her access to public reports, even though the “suicide” ruling closed any “compromising-an-ongoing-investigation” gap.

Courtesy Gail Wenhardt, findagrave.com

Courtesy Gail Wenhardt, findagrave.comNeal Townsend is buried at the Riverside Cemetery in Anamosa.

After four decades, she’s still searching for answers.

She knows he exposed fellow officers’ corrupt deeds. Did the information he held equal the liability he’d likely become?

One thing is certain: With his own blood, Neal Townsend paid for his courage and honesty.

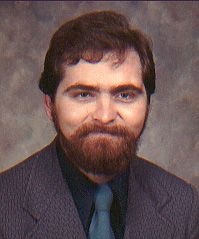

About Neal Townsend

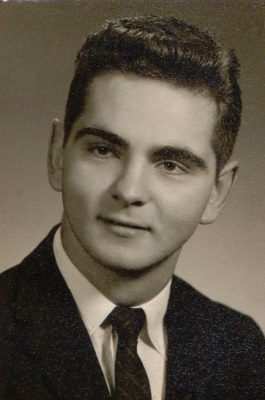

Neal Robert Townsend was born in Iowa May 5, 1946, to Neal and Matilda (McNurrin) Townsend.

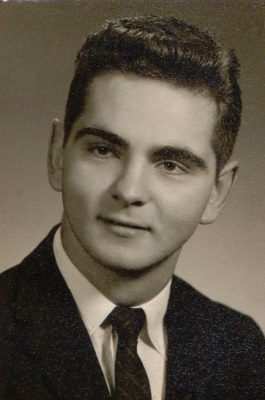

Neal Townsend graduation photo

Neal received his education and lived most of his life in Iowa, having moved to Idaho just two months before his death. He served as an officer with the Lava Hot Springs Police Department.

He died in his Lava Hot Springs apartment Tuesday, Sept. 2, 1975, at age 29.

Funeral services were conducted Friday, Sept. 5, at the Goettsch Funeral Home in Anamosa, Iowa, with burial at the Riverside Cemetery in Anamosa.

The Henderson Funeral Home handled local arrangements.

Information Needed

If you have any information about Neal Townsend’s unsolved murder, please contact the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) at (402) 493-8688, or email Omaha@ic.fbi.gov.

Sources:

- Amanda Wagner, personal correspondence to Iowa Cold Cases, ongoing

- Dawn Townsend Langer, personal correspondence to Iowa Cold Cases, ongoing

- Bannock County Sheriff’s Office, Idaho

- Lava Hot Springs, Idaho

- “Neal Townsend – What Happened?“A Facebook Memorial Page

- Neal Robert Townsend (1946 – 1975) — Find a Grave Memorial

- The Patty Hearst Kidnapping, the FBI Famous Cases and Criminals

- Letter of Denial sent to Dawn Townsend in response to Request to Examine And/Or Copy Public Records, from Bannock County Dept. Administrator Canda L. Dimick, letter dated July 31, 2000

- Letter to Dawn Townsend from Canda L. Dimick, City Clerk, City of Lava Hot Springs, Idaho. Dated July 28, 2000

- Appeal to subsection (a) (6) of the Freedom of Information Act, as amended (5 U.S.C. 552), from Dawn Townsend to Canda L. Dimick, letter dated June 31, 2000

- U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Bureau of Investigation letter from A. Robert Walsh, Legislative Counsel Office of Public and Congressional Affairs, to Ms. Dawn Townsend, letter dated June 22, 2000

- U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Bureau of Investigation letter from Special Agent in Charge David M. Tubbs to Dawn V. Townsend, letter dated January 3, 2000

- (Idaho) Governor Dirk Kempthorne letter to Dawn V. Townsend, dated December 13, 1999

- Letter to Dawn V. Townsend from Gordon F. Murri, Henderson-Cornelison Funeral Home, letter dated November 30, 1999

- “POLICE LOG: Former Lava Hot Springs police chief John Burris, 37, arrested,” The Idaho State Journal, Pocatello, Idaho, Monday, June 27, 1977, Page 2, Section A.

- “Resignations Asked of Two Lava Police,” The Idaho State Journal, Friday, August 13, 1976

- “Lava Names Acting Police Chief,” The Idaho State Journal, August 1976

- “Police in Lava Lose Evidence,” The Idaho State Journal, Tuesday, June 15, 1976, Page 2, Section A

- “Three Held in Lava Drug Heist,” The Idaho State Journal, Monday, June 14, 1976

- “Two Women Plead Guilty to Robbery,” The Idaho State Journal, Friday, October 10, 1975

- Village of Lava Hot Springs handwritten letter to Dawn Virginia Townsend and Robert Neal Townsend, from Pearl Hobbs, City Clerk, City of Lava Hot Springs, Idaho, September 24, 1975

- “Lava Slates Water Bid Advertisements,” by Mig Byington,” Idaho State Journal, September 12, 1975

- Neal Townsend Obituary

- “Former Iowan’s Death Is Ruled a Suicide,” The Cedar Rapids Gazette, September 3, 1975

- “Police Officer Found Dead,” Idaho State Journal, Pocatello, Idaho, September 2, 1975

- Certificate of Death, State of Idaho, for Neal Robert Townsend

- “Eight Marijuana Plots Discovered Near Lava,” The Idaho State Journal, July 3, 1975

- “Council Suspends Policeman Burris,” The Aberdeen Times, Page One, August 23, 1973

- “Police Chief Arrests Man for Drug Dealing,” The Idaho State Journal, undated article

- “Alcoholism Counselor Is Returning a Favor,” by Pat Peterson, The Cedar Rapids Gazette, Sunday, July 22, 1973

- “Branch Offices Established By Drug, Alcoholism Group,” by Pat Peterson, The Cedar Rapids Gazette, Sunday, July 22, 1973

- “Alcoholism Unit Expands Into Jones and Benton,” by Pat Peterson, The Cedar Rapids Gazette, Sunday, Jan. 28, 1973, Page 4A

My father died of alcohol abuse the work this young man was doing would probley have saved lot of people who suffer with this horrific addiction.